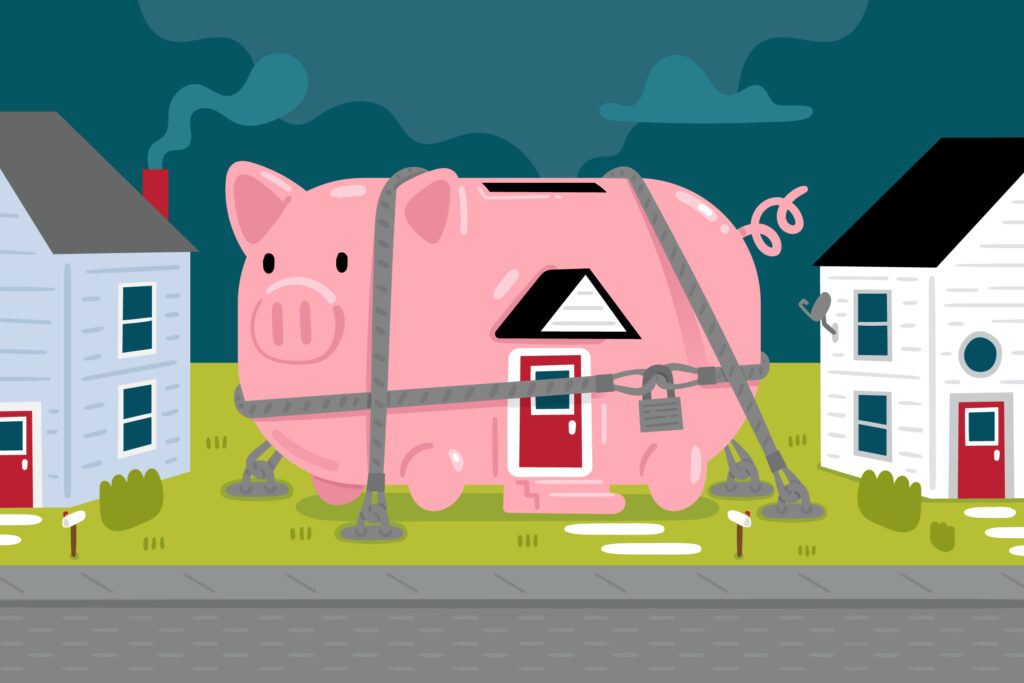

Homeownership is often seen as the gateway to generational wealth, but not all homeowners are able to unlock that wealth when it matters the most.

On average, Black homeowners face greater challenges in accessing their home equity, whether through home equity loans, cash refinancing, or home equity lines of credit (HELOCs).

A recent study found that Black borrowers were denied home equity credit more often, costing them access to $11.2 billion between 2018 and 2021.

“The way to build wealth for most families in the U.S. is through home ownership,” said James Conklin, ARK Professor of Real Estate at the Terry College of Business. “What happens if you have home equity, but you can’t access it? That affects things like starting small businesses or covering educational expenses … So if the experience is different for minorities and whites, then this source of wealth and how you can use it is very different.”

Conklin worked with economist Kristopher Gerardi at the Federal Reserve Bank of Atlanta and Lauren Lambie-Hanson at the Federal Reserve Bank of Philadelphia to analyze a new trove of home equity loan application data collected under the Home Mortgage Disclosure Act (HMDA). Their Journal of Financial Economics paper “Can everyone tap into the housing piggy bank? Racial disparities in access to home equity” was published in June 2025.

The study was made possible by a 2018 HMDA change that required lenders to track application information for homeowners applying for home equity loans and HELOCs.

This anonymized data — borrowers’ income, credit scores, ZIP codes, debt-to-income ratios, race, gender and age — has long been collected for home mortgages but was not available for home equity products until 2018, Conklin said.

Conklin, Gerardi and Lambie-Hanson were the first team to analyze this new pool of lending data.

They examined loans applied for between 2018 and 2021. Of the more than 12.6 million applications filed nationwide, they found Black homeowners are 9 percentage points more likely than white borrowers to be denied.

Hispanic and Asian borrowers were 4 percentage points and 1 percentage point, respectively, more likely to be denied than white borrowers.

The difference meant Black homeowners lost access to $11.2 billion in equity over the three-year study period.

A similar calculation shows Hispanic applicants could have extracted an additional $8.8 billion in equity and Asian applicants an additional $8.5 billion.

Explaining the Differences

When Conklin and his team examined the application data further, they found nearly 75% of the disparity between Black and white homeowners’ borrowing ability could be explained by traditional underwriting variables such as credit score and debt-to-income ratio.

However, the remainder of the disparity cannot be explained by the numbers in loan applications.

“Although rejection rates are different because of this widespread difference in credit scores and debt-to-income ratios, that isn’t the full story. We still find decent-sized gaps between minorities and whites in rejection rates after we control for credit score, loan-to-value ratio and debt-to-income ratio,” Conklin said.

“Minorities are still more likely to be rejected on equity withdrawal products.”

These disparities aren’t apparent in the home-buying mortgages market because most run through automated underwriting systems backed by Fannie Mae and Freddie Mac.

“With first mortgages, you plug in a whole bunch of information into the computer and then it spits out whether this loan is a good idea,” Conklin said. “It’s very standardized, and everybody in the industry kind of uses the same thing.

“But for home equity loans and for HELOCs, lenders often use their own internal systems.”

Different lenders use different systems requiring different information with different levels of subjectivity, Conklin said.

Homeowners are also more likely to meet with a banker in person to apply for home equity products, and some conscious or unconscious bias could be introduced into the system there, he added.

Impact of Equity Access

Whether access to homeowners’ equity is hindered by financial factors or bias, the loss of access to this important funding source has a chilling effect on the ability of minority homeowners to fund home repairs or expand small businesses. It also has a chilling effect on the economy.

Since 2019, housing prices have soared by 60%, leaving American homeowners with about $33 trillion in aggregate housing wealth, according to Conklin’s paper.

That’s a windfall for homeowners and the economy at large — but only if they can tap into it.

“You’ve got this source of wealth,” Conklin said. “But the question of how easy it is to access that source of wealth when you need it — for whatever the case may be — is an important thing. It changes the nature of the asset and of the wealth.”