If you’re not paying for a service — so the saying goes — you are the product being sold.

It was true in the 1920s, when families started to tune in to sponsored radio shows, and it’s true today, as marketing companies vacuum up data about our online shopping, browsing and social habits to target advertisements.

But does privacy have to be the price of free internet content? Maybe not, according to a recent study by Terry College marketing researcher Pengyuan Wang and George Washington University marketing researcher Li Jiang.

Wang studied the impact on online advertising in the wake of the European Union’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) rules that severely limit how websites collect and use user data and require explicit user consent before websites gather any data.

While Wang’s findings were important for publishers operating in the European Union, the same changes soon might be coming to the U.S. Several states passed data privacy laws, such as the California Consumer Privacy Laws and the California Privacy Rights Act amendments that went into effect this year. Many websites have begun asking all users (whether based in the EU or not) for explicit consent to track their data.

The impact on advertising placement prices wasn’t as dire as projected, Wang found. Her paper, “The Early Impact of GDPR Compliance on Display Advertising: The Case of an Ad Publisher,” was published this spring in the Journal of Marketing Research.

“I think the industry was super pessimistic about the regulations in 2018,” Wang said. “the argument was, ‘If I don’t get your personal data, I will lose the performance of my ads, so I will lose a lot of ad revenue. Without ad revenue there is no way that I can provide free content to the internet users.’ At that time, there was a sentiment that it was the end of free internet.”

Wang and coauthors studied advertising performance and prices of a large international publisher. In 2018, when the GDPR went into effect, the publisher began to request explicit consent from users with EU IP addresses to collect and use their personal data for advertising. Wang’s team analyzed 3.7 billion ad impressions from around 6,000 ads placed on the publisher’s site five weeks before and five weeks after the publisher instituted its GDPR compliance plan.

After the publisher asked for consent to collect and use data to target ads, the number of conversions per click fell by around 5%, compared to the pre-GDPR average. The bid price advertisers were willing to pay for each click fell by 6%.

“The publisher I studied in my paper saw a less than 10% reduction in ad performance and revenue, so it’s a substantial drop — but not the catastrophic 20% or even higher drop opponents were predicting,” Wang said.

One reason for the limited reduction in ad revenue was most of the publisher’s readers simply consented to have their data used to target ads.

“People received many consent requests when publishers rushed to implement GDPR’s requirements,” Wang said. “After a while, they may just get tired and give up looking into the details. So consent rates were not as low as what we thought they would be.”

Wang also noted the reduction in ad performance and payment varied greatly according to product category. Broad interest categories, such as retail and consumer products, fared better than ads for travel or financial products. In general, the more niche the product or service offered was, the worse the ad fared without data targeting, Wang said. However, when niche ads displayed with articles with similar themes, they were much more successful.

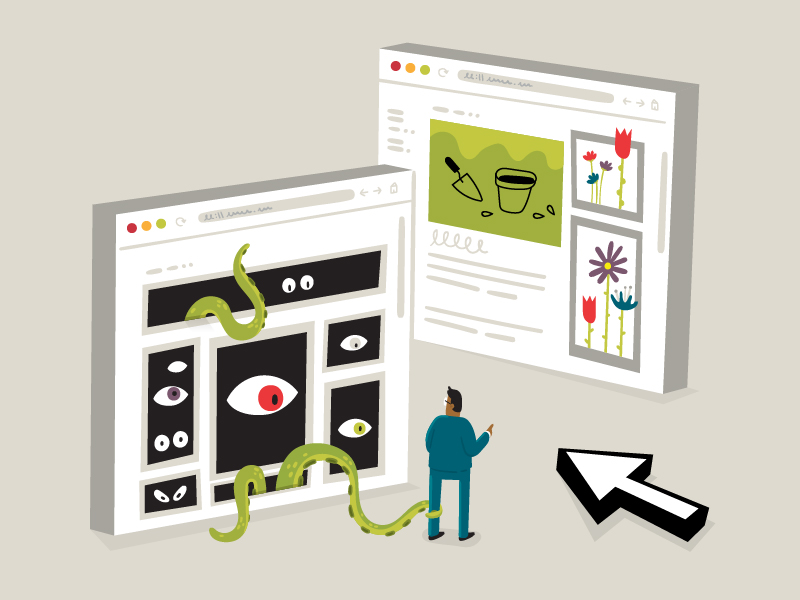

This is “contextual ad targeting,” which was the model driving traditional magazine and newspaper advertising. The idea is advertisers would place an ad for a credit card next to an article about how to build a better credit rating.

This type of marketing will become increasingly vital as restrictions on data tracking progress, she said.

“I think about it as a renaissance for contextual advertising,” she said. “Before we had all of this personal data, before the internet, we had magazines. Every magazine out was doing contextual targeting. After we started behavioral targeting based on personal data, we kind of shifted to personal data.”

Publishers should lean into developing systems to pair ads with content that attracts the same consumers they’re marketing to, she added.

“The problem for the publishers is they have great content, but they need to sell them to the right advertisers,” she said. “after the GDPR, they really have to tag their web pages with advertisers in mind and provide such information in ad auctions. It is feasible, especially with the help of AI tools such as natural language processing.”